Northwest Passage

Rule Britannia!

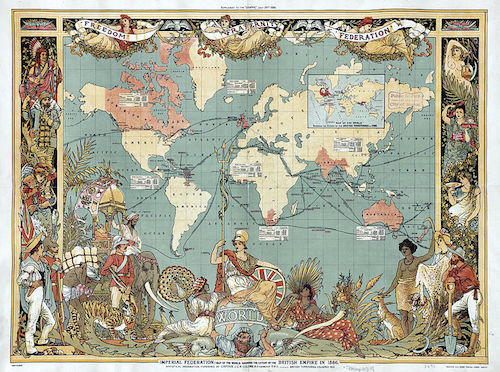

By the time Franklin sailed in 1845, Great Britain had emerged on the world’s stage as a leading power. By that date it was the most industrialized country in the world. Its manufacturing plants were supplying the world with a wide variety of products, from cotton fabrics, cutlery and crockery to steel, locomotives and specialized gaslight technologies. Partly as a result of its rapidly growing commercial wealth, by 1845 Britain had achieved global naval supremacy, demonstrated by winning the Napoleonic Wars by 1815. At a time when most international trade was by ship, its strong navy helped, in turn, to ensure that it could trade throughout the world’s waters. Just a few short years after Franklin’s departure for the Arctic, Britain showcased to the world its commercial dominance and technological superiority in London's Great Exhibition of 1851, the first World’s Fair. The search for the Northwest Passage connected closely to these larger contexts of British imperial ascendancy.

Map of the World Showing the Extent of the British Empire in 1886.

Map of the World Showing the Extent of the British Empire in 1886.

Satellite Photograph - Great Britain and Ireland

Satellite Photograph - Great Britain and Ireland

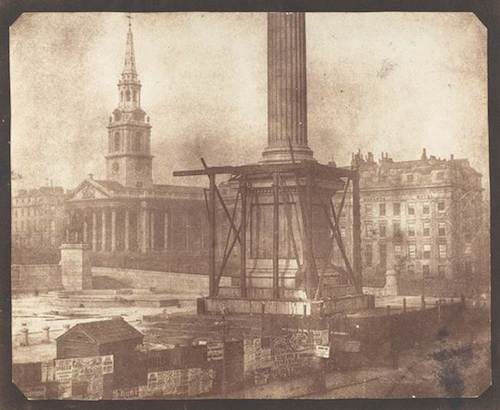

Nelson's Column, April 1844: Britain celebrated the 1805 Battle of Trafalgar with

the erection of Nelson's Column in London's Trafalgar Square.

Nelson's Column, April 1844: Britain celebrated the 1805 Battle of Trafalgar with

the erection of Nelson's Column in London's Trafalgar Square.

Why the NorthWest Passage?

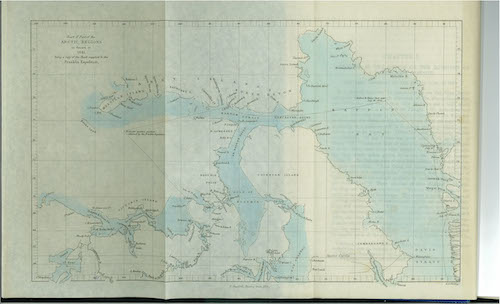

Europeans, particularly the British, relied on trade routes to India and China that involved a long voyage around the tip of South America. This was inhibited by the Spanish dominance of South America. Britain had long dreamed that there would be a shorter passage for ships around the north of North America. Captain Cook had been sent looking in 1778 and George Vancouver in 1792. The search resumed at the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 and between then and 1840 Britain sent at least 13 naval expeditions searching to find a Northwest Passage through the Arctic regions of what is now Nunavut. Britain also sent several overland expeditions led by such notable explorers as George Back, Peter Dease, Thomas Simpson, John Rae, and before his ocean expedition, John Franklin. While they added considerably to the mapping of the Arctic the main prize still eluded them – an imagined passage through the Arctic archipelago affording a more direct route between Europe and Asia.

The Need for Mapping

Through the expanding role of its navy, Britain was increasingly coming into contact with the larger world, many parts of which were not known to European countries. In the nineteenth century the Royal Navy placed an emphasis on mapping the continents and understanding the world's environments on which navigation and trade depended. Science was key to Britain's development and operated hand in glove with naval, industrial and commercial expansion. The goal of geographical discovery required sound science for safe navigation, which depended on reliable theories of geomagnetism, ocean currents, and tides. When Britain renewed its search for the Northwest Passage in 1818, science, especially magnetic science, was a central component in all the expeditions it sent to the Arctic. Both the Passage and the concept of stable geomagnetic forces were largely imaginary concepts – abstractions that needed to be tested in the field to see if their underlying assumptions were warranted.