Arctic Homeland

Rocks and Ice 1 by Sue Shirley, used with permission

Rocks and Ice 1 by Sue Shirley, used with permission

Franklin’s final voyage took him to a part of the Arctic that was homeland to the Natsilingmiut [Netsilingmiut, Netsilik, Neitchillie]. These were the Inuit living in the region between north-western Hudson Bay and King William Island. They shared some elements of their culture, society and economy with other Inuit groups and circumpolar populations, and had patterns distinctive to this region.

The Arctic has been a homeland for a succession of First Peoples for thousands of years. For those who have the knowledge and skills to live there, the Canadian Arctic is a rich and beautiful land. Before modern times, intimate knowledge of the climate and geography has been crucial to human survival in any place on earth. Intimate knowledge of the environment has been particularly crucial and exacting in the Arctic, situated in high northern bands of latitude and mostly above the tree line, and characterized by a cold climate, long dark winters, short light summers, and the almost endless lakes and granite rocks of the Canadian Shield. The climatic conditions can be extreme and change rapidly. Inuit have relied, therefore, on deep knowledge of vast areas of land and sea to find what they needed to thrive in this magnificent place.

King William Island, view from space, NASA, 2 September 2005

King William Island, view from space, NASA, 2 September 2005

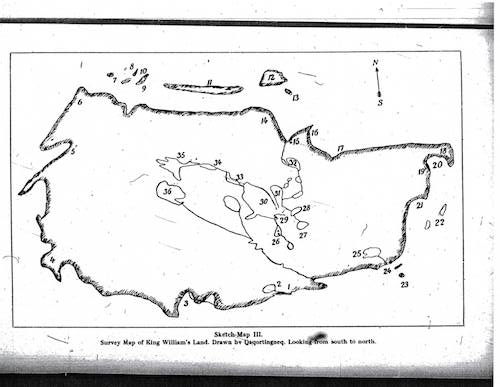

Map of King William Island by Qaqortingneq, 1920s

Map of King William Island by Qaqortingneq, 1920s

Organizing themselves into small, mobile communities, Natsilingmiut responded on a daily and seasonal basis to each other, and to the natural environment, its resources and opportunities. Inuit culture grew up around alertness, skill, knowledge, co-operation and adaptability.

Inuit also developed some very specific technologies to allow them to adapt to the environment, from the iglu (snow house) and the qajaq/qayaq (kayak), to the qulliq (seal oil lamp) and particularly warm and dry clothing, such as atigi (warm parka) and amauti (warm garment for mother and infant child) and kamiit (waterproof skin boots).

Hunting and Fishing (for food, heat, light, and transportation)

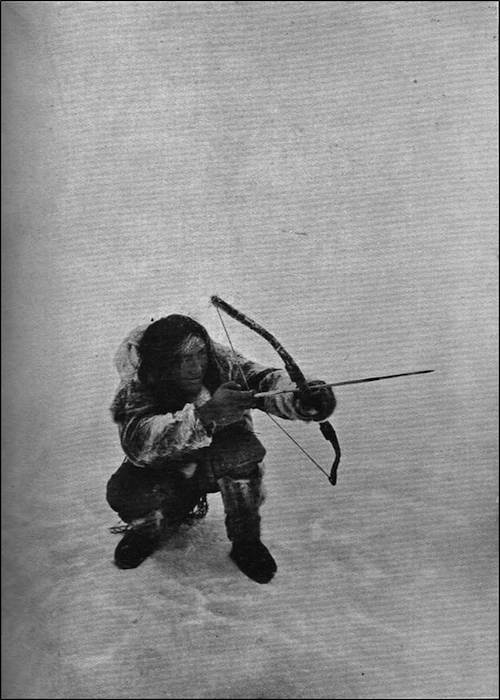

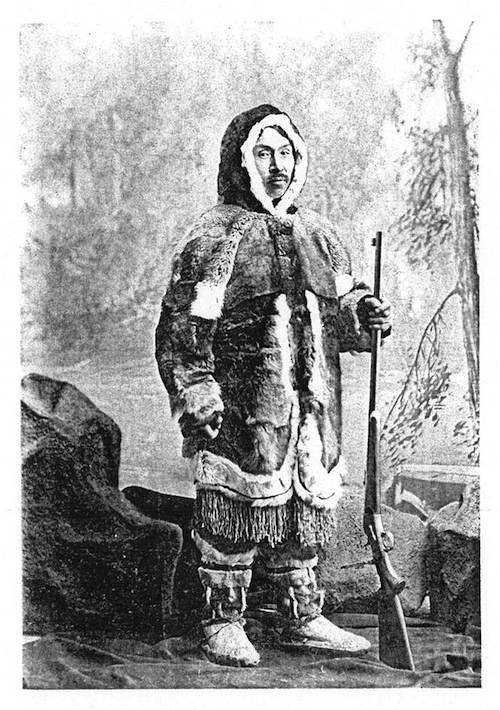

The Inuit were skilled hunters, and caught food year-round, even during the harsh winters. Every part of the animal had a use. Sea mammals, such as seals and walruses, were hunted all year round. These provided not only food, but sealskin and other animal skins were used to make clothing, and materials for boats, tents, and harpoon lines. Seal skins were also used to make floats, that kept the marine mammals afloat after they had been harpooned. Seal fat provided the fuel for light and heat for cooking and drying clothes. Walruses were hunted for meat (for people and dogs) and the ivory tusks were used for needles, ornaments, amulets, knives and other tools. Whales (narwhals and beluga) provided food for people and dogs, and whale bones were used to make tent supports, qamutiik (sleds). Polar bear, which was hunted on the ice or on the land, provided valuable fur and meat. Fish, particularly arctic char, was an important source of food year round. The Inuit also hunted a variety of land animals including caribou, muskoxen, arctic fox, and arctic hare. Inuit also hunted a number of birds, including ducks, geese and ptarmigan.

Knife- muskox horn handle; bone blade

Knife- muskox horn handle; bone blade

An ulu in the western Arctic style

An ulu in the western Arctic style

Housing

Natsilingmiut maximized opportunities by utilizing the limited range of materials for building, including stone, sod for winter houses, driftwood and whalebone for tent supports, sled frames and qajaq/qayaq (kayak), around which they stretched skins, and snow for iglu dwellings for winter shelter or while on the trail.

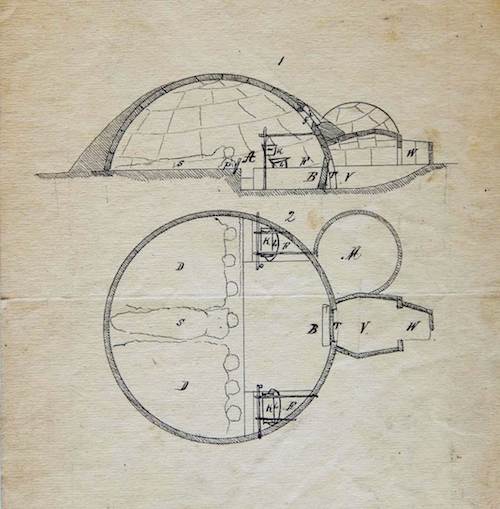

Cross-section of a Natsilingmiut igloo

Cross-section of a Natsilingmiut igloo

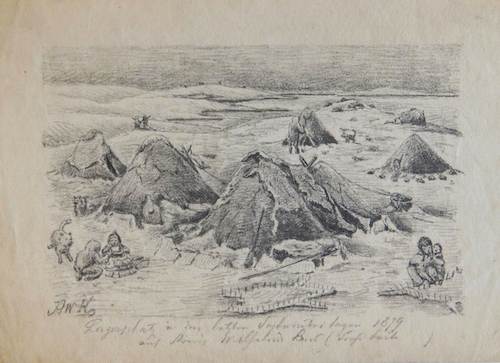

Drawing of Inuit Tupik encampment

Drawing of Inuit Tupik encampment

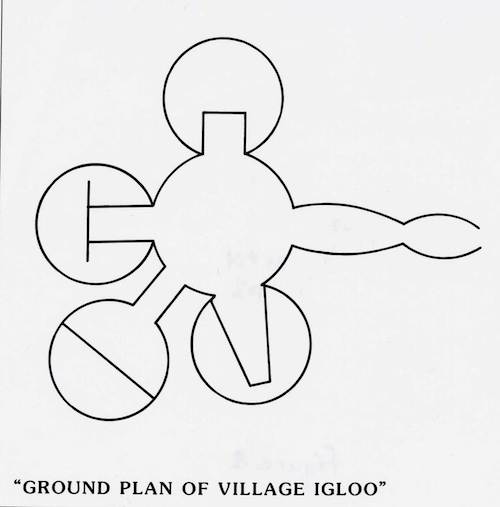

Ground plan of the Village Igloo

Ground plan of the Village Igloo

![Inuit group at camp on ice, Gjoa Haven, King William Island, NWT [Nunavut]](../archive/imageImages/500/InuitGjoa.jpg) Inuit group at camp on ice, Gjoa Haven, King William Island, NWT [Nunavut]

Inuit group at camp on ice, Gjoa Haven, King William Island, NWT [Nunavut]

Transportation

Inuit developed a light-weight material culture and seasonal strategies of travelling by foot, by qamutiik (dog team sled), qajaq/qayaq (kayak) and umiaq (a boat that carries a number of people, often women and children) across vast expanses of land and sea for the animals which provided food, clothing, bones for sledges, and seal fat for lamps.

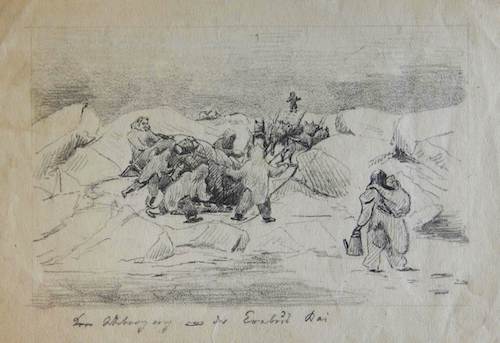

Loading Seal, Netsilik Fiord – “Akatooga”

Loading Seal, Netsilik Fiord – “Akatooga”

Inuit party and dog team at Erebus Bay

Inuit party and dog team at Erebus Bay

Inuit man and his kayak at Killineq (Port Burwell) Nunavut

Inuit man and his kayak at Killineq (Port Burwell) Nunavut

Sewing

Inuit women, girls and men knew how to scrape, clean and prepare skins to make tents and an array of warm clothing. Just one example was their skill in making water-tight boots to prevent wet feet, an outcome that could easily lead to death.

Inah-loo (inaluk) sewing skin kamik, Etah northern Greenland

Inah-loo (inaluk) sewing skin kamik, Etah northern Greenland

Illustrated London News, “Captain McClintock’s First Interview with the Esquimaux at Cape Victoria” (wood

engraving)

Illustrated London News, “Captain McClintock’s First Interview with the Esquimaux at Cape Victoria” (wood

engraving)

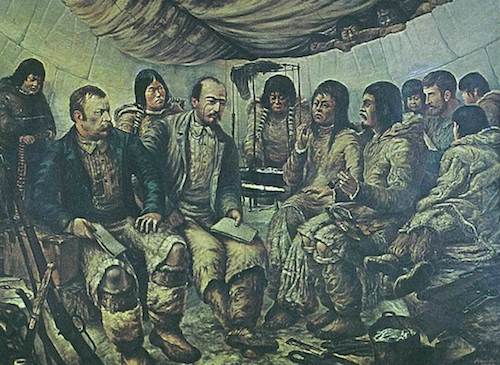

Frederick Schwatka and companions meeting with members of Netsilingmiut in the Arctic,

ca. 1880

Frederick Schwatka and companions meeting with members of Netsilingmiut in the Arctic,

ca. 1880

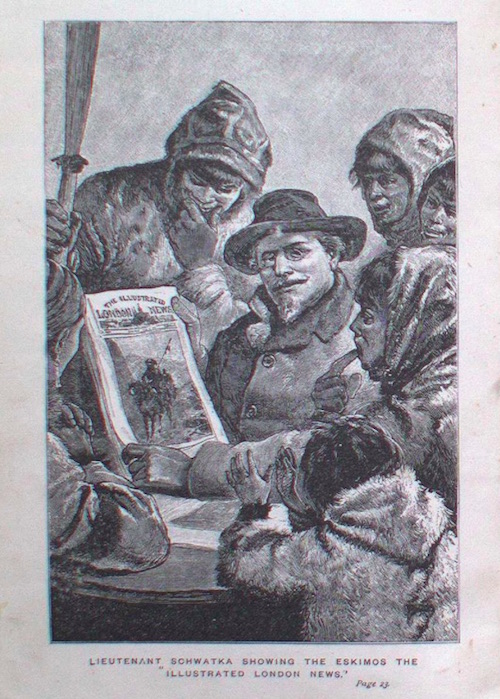

Lieutenant Schwatka showing the Eskimos the Illustrated London News

Lieutenant Schwatka showing the Eskimos the Illustrated London News

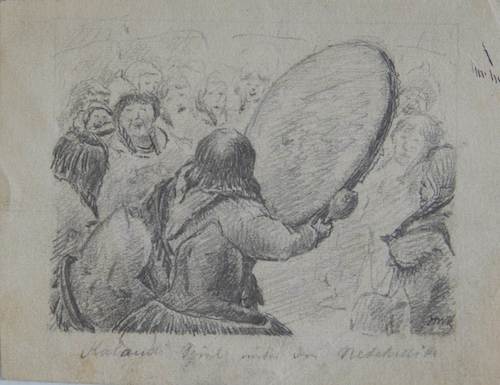

Inuit Qaujimajatuqangiq

From one generation to the next Inuit men and women passed on the essential skills, knowledge and values (Inuit Qaujimajatuqangiq (IQ) – knowledge long known) to enable them to develop isuma (wisdom) in order to adapt and learn from the environment, and thrive.

![Inuit Man and his Kayak at Killineq (Port Burwell) [Nunavut]](../archive/imageImages/thumbnail/InuitKayak.jpg)