The Final Days of the Franklin Expedition: New Skeletal Evidence (1997)

Reports of cannibalism occurring during Franklin's third expedition first surfaced in 1854, when Dr. John Rae, who was conducting a survey of the central Arctic coastline, encountered at Pelly Bay an Inuk named In-nook-poo-zhe-jook, who told him that six years earlier, a group of 35 to 40 Europeans had been seen pulling a sledge and boat down the coast of King William Island and that their bodies had later been found near Starvation Cove (Neatby, 1970:245, 354). More shocking to Rae were Inuit reports that the bodies had been cannibalized (Neatby, 1970:245; Klutschak, 1987:xxiv).

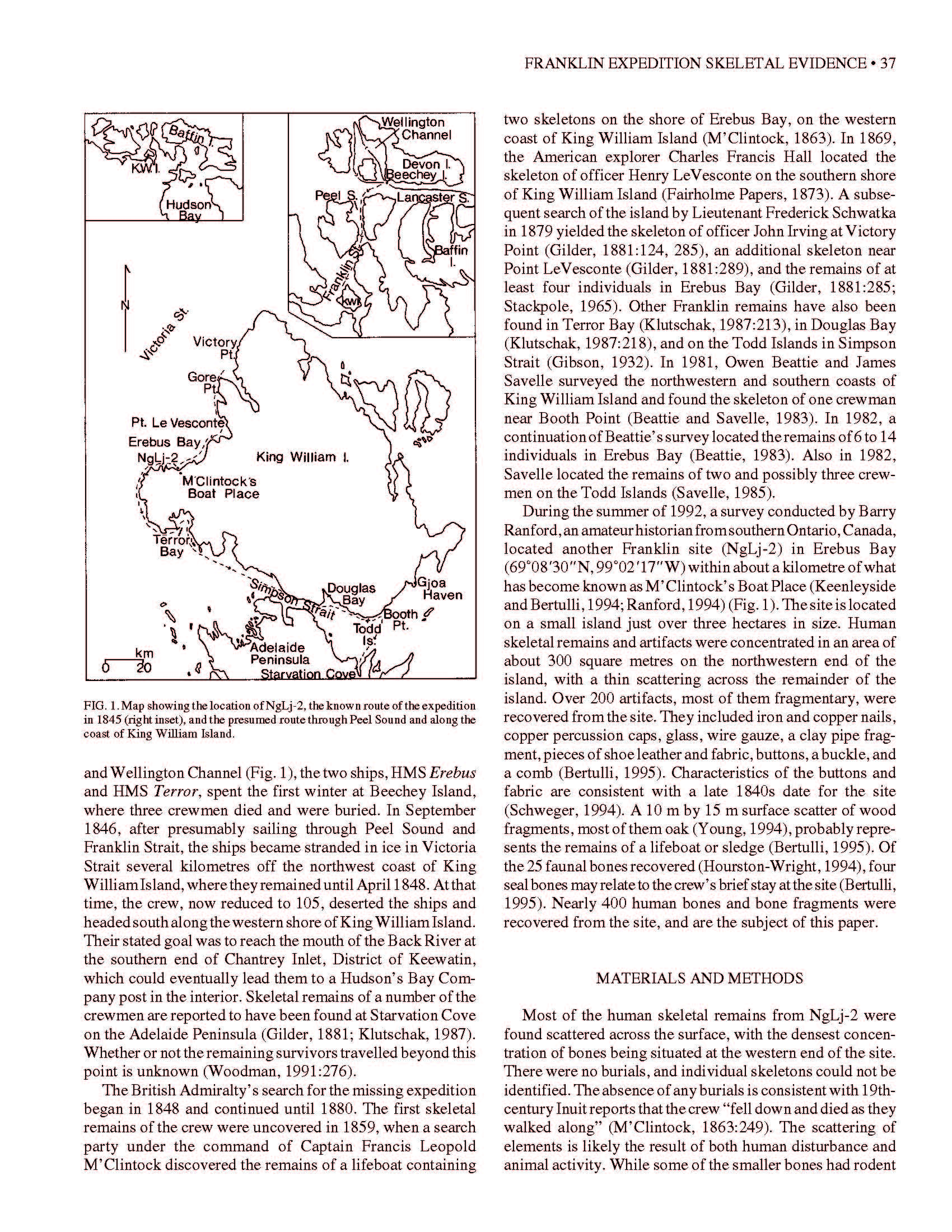

[...]

Despite public opposition to Rae's account, Inuit stories of cannibalism among Franklin's crewmen continued to surface. In 1869 [...] the American explorer Charles Francis Hall encountered Inuit who gave him eyewitness accounts of cannibalism among Franklin's men. In one account, the Inuk In-nook-poo-zhejook spoke of seeing some "long boots" that "came up high as the knees and that in some was cooked human flesh — that is human flesh that had been boiled" [...] In another account, an Inuk named Eveeshuk described "one man's body when found by the Innuits flesh all on and not mutilated except the hands sawed off at the wrists — the rest a great many had their flesh cut off as if someone or other had cut it off to eat"

[...]

Similar accounts of cannibalism among members of the Franklin expedition were gathered by Lieutenant Frederick Schwatka, who conducted a search for the missing crew on King William Island in 1879. According to one report, an Inuk named Ogzeuckjeuwock "saw bones from legs and arms that appeared to have been sawed off … The appearance of the bones led the Inuits to the opinion that the white men had been eating each other … His reason for thinking that they had been eating each other was because the bones were cut with a knife or saw."

Such accounts were the only evidence that cannibalism occurred on the expedition until 1981, when Beattie discovered cut marks on the shaft of a right femur recovered from a Franklin site on the southeastern coast of King William Island (Beattie, 1983). In addition to the cut marks, Beattie found that the skull of the same individual showed evidence of having been intentionally broken. Other signs that cannibalism might have occurred included the fact that most of the bones recovered from the site were limb bones, possibly retained as a "portable food supply" (Beattie and Geiger, 1987:62), and the fact that many of the bones were found clustered outside a tent circle, as if intentionally deposited there (Beattie and Savelle, 1983).

[...]

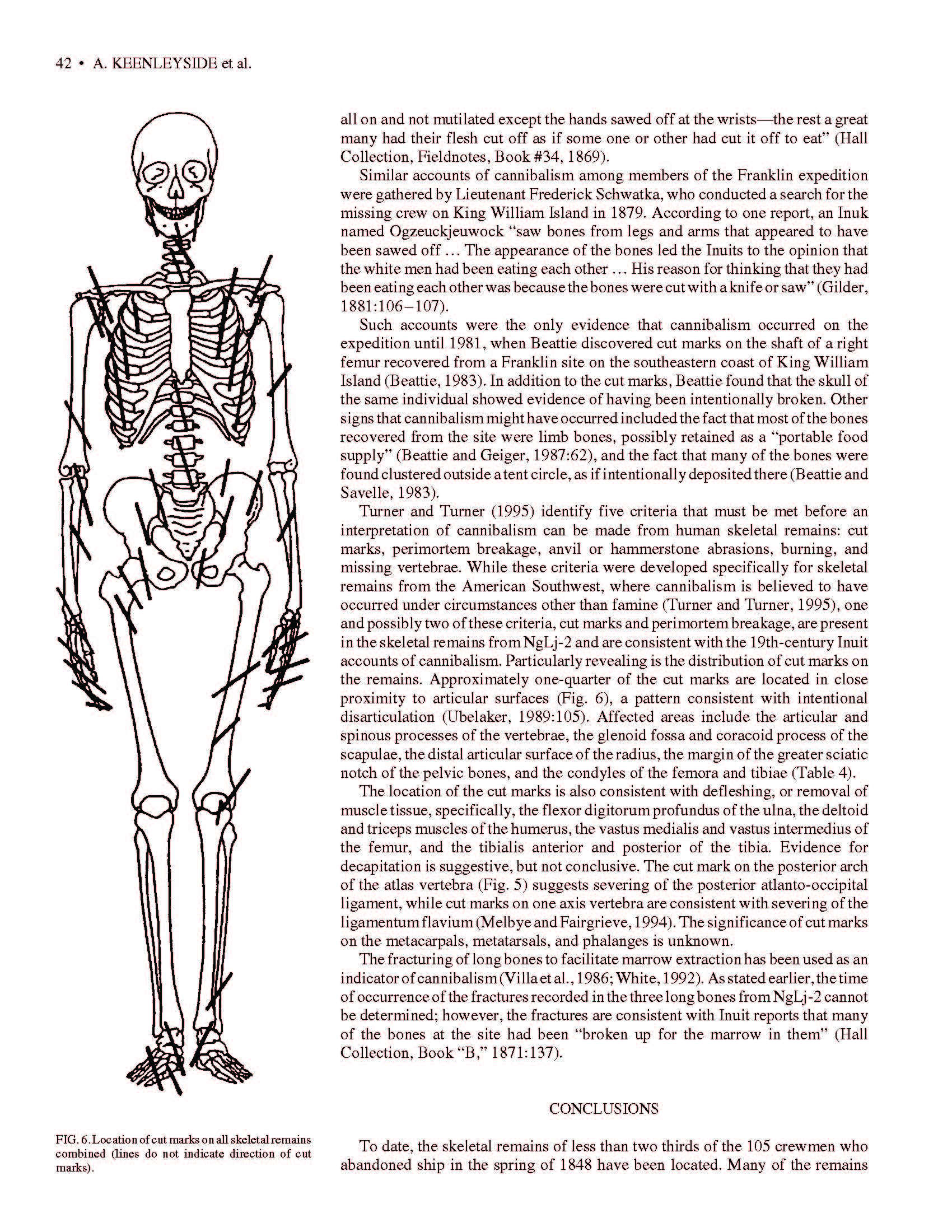

Particularly revealing is the distribution of cut marks on the remains. Approximately one-quarter of the cut marks are located in close proximity to articular surfaces, a pattern consistent with intentional disarticulation (Ubelaker, 1989:105).

[...]

The location of the cut marks is also consistent with defleshing, or removal of muscle tissue, specifically, the flexor digitorum profundus of the ulna, the deltoid and triceps muscles of the humerus, the vastus medialis and vastus intermedius of the femur, and the tibialis anterior and posterior of the tibia. Evidence for decapitation is suggestive, but not conclusive.

[...]

The fracturing of long bones to facilitate marrow extraction has been used as an indicator of cannibalism (Villa et al., 1986; White, 1992) [...] the fractures are consistent with Inuit reports that many of the bones at the site had been "broken up for the marrow in them" (Hall Collection, Book "B," 1871:137).

CONCLUSIONS

To date, the skeletal remains of less than two thirds of the 105 crewmen who abandoned ship in the spring of 1848 have been located.

[...]

Elevated lead levels in the remains are consistent with previous measurements (Beattie and Geiger, 1987; Kowal et al., 1989) and support the conclusions of Beattie and colleagues (Beattie and Geiger, 1987; Kowal et al., 1989, 1991) that lead poisoning had greatly debilitated the men by this point. The presence of cut marks on approximately one-quarter of the remains supports 19th-century Inuit accounts of cannibalism on the expedition.